いのちを守る人を育てる

国際保健活動

と政策提言・普及啓発活動

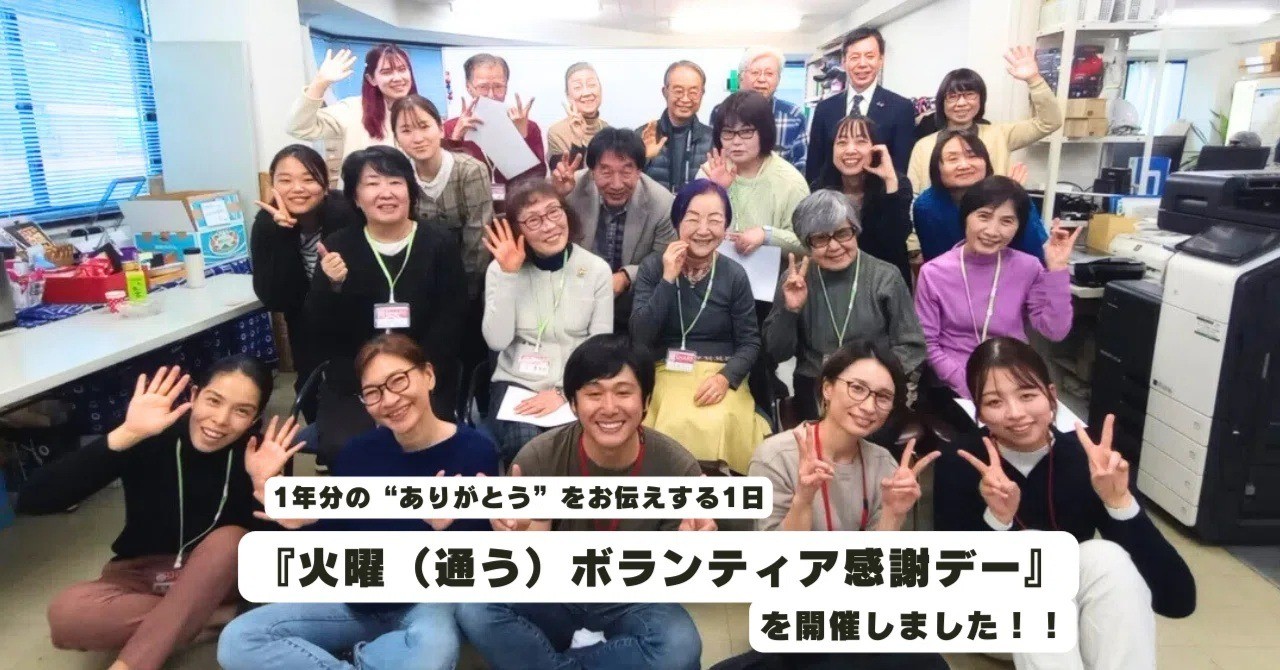

国際協力NGOシェアは、すべての人々が健康に暮らせる世界の実現を目指して、

プライマリ・ヘルス・ケアの観点から、いのちを守る人を育てる取り組みをしています。

活動の軸は、基盤をつくる「国際保健活動」と、仕組みを変える「政策提言・普及啓発」の2つです。

健康の基盤をつくる

国際保健活動

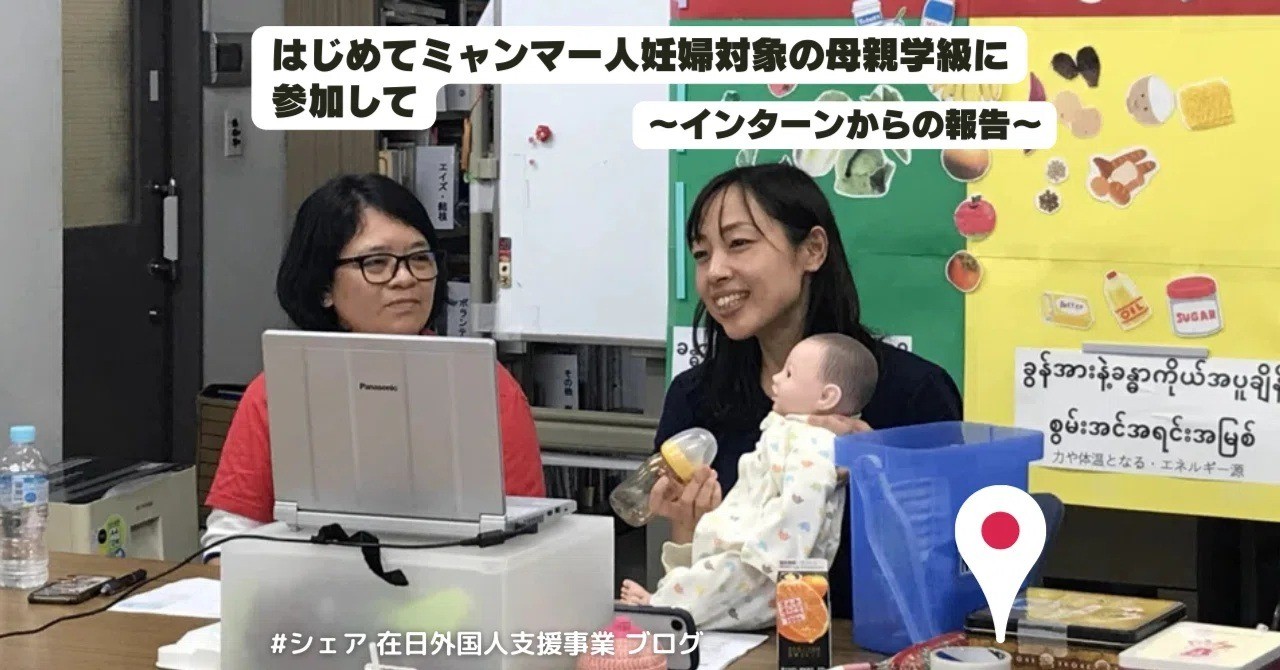

いのちを守る人を育てる国際保健活動をカンボジア・東ティモール・日本で取り組んでいます。プライマリ・ヘルス・ケアの観点を重視し、現地の人々が自分たちで自分たちのいのちを守ることが持続的におこなわれることを目標としています。

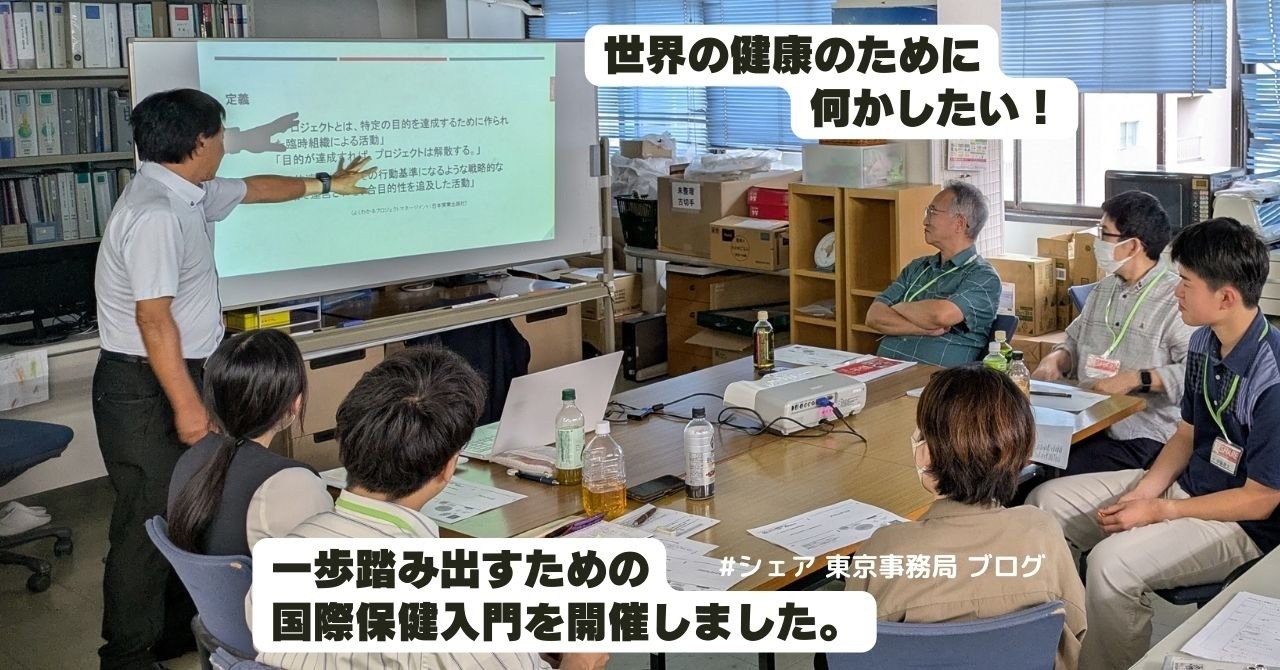

健康を取り巻くしくみを変える

政策提言・普及啓発活動

すべての人々が健康に暮らせる世界の実現を目指して、健康や保健に対する社会のしくみや人々の考えから変えていく政策提言・普及啓発活動にも取り組んでいます。